4 RPGs and What They Taught Me About Writing

- Uncategorized

- October 22, 2024

I’m not a writing advice guy. There are a lot of writing advice guys out there, and a small number that will tell you practical, actionable things that you can put into practice, but in my experience, the vast majority of it is somewhere between Draw The Rest of the Fucking Owl and just… vibes. Most writers, including extremely talented professionals, do not fully understand what they do or how they make it work beyond the process that works for them, but most writers also need alternative income streams, so the world does not need another writing advice blog.

So feel free to rename this blog “4 bad writing habits I picked up from RPGs” if you like.

But at the end of the day, any RPG is an act of communal storytelling, and unlike basically any other form of storytelling, you are interacting with and seeing the reactions of your audience in real time as the story unfolds.

So, since I have recently published a story that takes place almost entirely during the playing of a tabletop roleplaying game (Fermi’s Wake: D & Deception, available at Amazon and Scarlet Ferret), it seems like a good time to go back and see what, if anything, I actually learned about writing playing those games.

Star Trek PbEM RPGs: Give People a Reason to Give a Shit

The first writing I ever did for an audience that was not a teacher or parent, was online as part of a collective “Play by Email” roleplaying game. Barely even a game, it was a vast, collective piece of fanfiction, where every player created and wrote a different member of the crew of a Federation starship crew. The Captain/GM would kickstart the adventure, telling you where the ship was and its mission, and in one massive and unwieldy email chain, people would reply all telling everyone how their character was responding and progressing the story. There were a lot of players, which meant the ranks filled up quickly, which meant that mostly this game was training me up to eventually write the Star Trek: Lower Decks Crew Handbook.

But it was also the first time I saw properly honest feedback on my writing. This wasn’t a workshop – nobody was rating or critiquing your use of language or character. But there were a lot of players, and at its highpoint you’d find dozens of emails in your inbox in one evening.

And not everyone was completely fastidious about reading everyone else’s work. A good two or three years before Google’s page rank system hit the mainstream, you learned to judge the success of a given post by how many posts appeared that acknowledged or reacted to the events you’d written about. And often the most successful posts were the ones that gave people stuff to react to. A deep dive into your character’s backstory? That gives people nothing. Your character coming up with an ingenious plan that immediately goes terribly wrong? Suddenly you’re setting off a chain reaction.

But above all, it taught me to value the reader’s time. To write fiction is to demand someone give up their free time to listen to you talk at length. After those old email games, I have always stopped to wonder what exactly is in it for them.

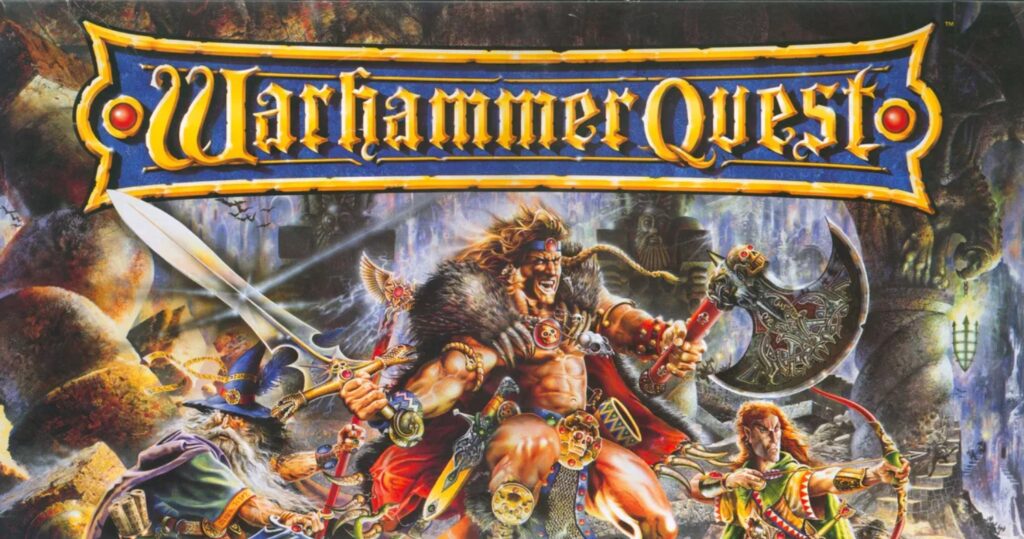

Warhammer Quest: Stakes Aren’t Everything

Tried Dungeons & Dragons early and immediately bounced off it hard. Games Workshop’s Warhammer Quest was much more my speed. Good old hack-and-slashing dungeon crawling gameplay, with thick, sturdy interconnecting floor pieces to map out your dungeons, and a great way to repurpose your and your friends’ Warhammer armies.

When we tired of the roguelike, deck-generated dungeons, we began to rotate DM duties. I ended up in the DM chair perhaps a bit more than my share, either because my adventures were the more widely enjoyed, or because I simply wanted it more.

Our interpretation of the rules was fast and loose, leaving our wizard’s resurrection spell so OP that the party once got past an ingenious portcullis trap I had planned by dicing one another into cubes, posting the bits through the gaps and then resurrecting them on the other side. (I allowed it).

But the game that sticks with me is one where we had wandered not far into the dungeon, and I said “Wait a second. This isn’t all a plan by an evil mage to open a portal to the Chaos realm is it?”

The DM, a friend’s younger brother, looked at me aghast. Had I been peeking at their notes?

I had not. It was always an evil mage trying to open a portal to the Chaos realm. Honestly, it was a bit of a dick move for me to point it out.

But from that point on, Chaos portals were out (except occasionally, as a treat). Instead, there were tower sieges, spy stories, treasure hunts, and nautical adventures. The goal became variety, to do something that the party hadn’t seen before, rather than to do the Biggest and most Epic adventure. This is where I learned to love The Gimmick, a love that drove the gimmick-of-the-week idea behind Fermi’s Progress.

In a way, this goes back to the first lesson. It’s not enough to save the world. You have to ask why we care if it gets saved.

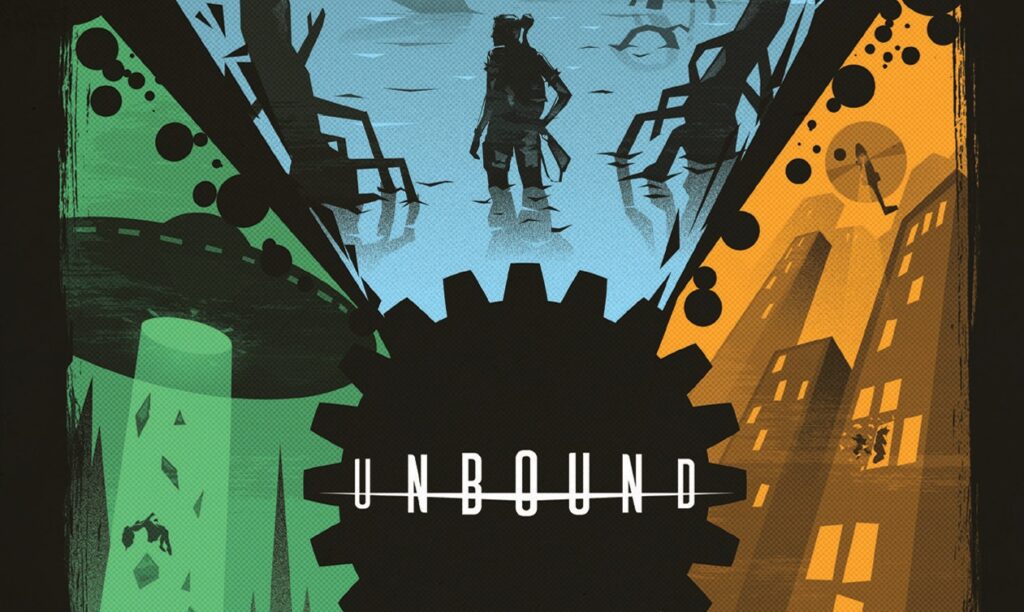

Unbound: Your Ensemble is a Character

Rowan, Rook and Deckard are probably best known for either Spire: The City Must Fall (which I’ve written the odd thing for) or Honey Heist. Both games are, in their own way, built upon intricate worldbuilding, whether it is a monstrous steampunk noir dystopian fantasy setting or a world where criminal bears wear hats. But before all of that, they created Unbound. It was a game system powered by a deck of cards you don’t mind ruining, with a light rules system and literally no worldbuilding or setting, primarily designed to get you into lots of cool fight scenes.

There is no planning ahead of time – the world and the story are crafted by all the players on the fly.

We played a game that revolved around a class of uplifted animal boarding school students in a zeppelin city in a solar punk post-human future.

But as well as being a fun game, Unbound also works pretty well as a writing guide. Its lists of touchstones and inspirations will get you immediately excited for the possibilities. What it has to say about establishing the stakes of your story is as useful for writing your own stories as it is setting up a good fantasy scrap. And it is particularly good when it comes to assembling an ensemble cast.

Tabletop RPGs, particularly in the traditional DnD mould, are always a bit crap at ensembles to be honest, despite it being the foundation of the game. Everyone comes up with their own character, backstory, and agenda. Then, because the DM says so, the characters meet in a tavern and decide to go kill a dragon together.

If the goal is to create a motley crew, that’s great. Except that most motley crews aren’t just a bunch of random people. As we recently covered, a band of misfits takes a bit more work than that.

But Unbound starts the players off by asking them to collectively pick a core and answer a bunch of questions related to it. By knowing what they want, what they’re scared of, and what their collective damage is, you can create an actual ensemble, rather than five competing protagonists.

Pathfinder: How to Write an Argument

Dialogue’s great isn’t it? I love writing dialogue. Two people, talking, arguing, fighting, flirting, whatever you like. Switch up the power dynamics, pull a dramatic reversal, and make a big reveal. So much fun to be had. You can even have a third person there, to interject every so often and spice things up.

But then you get to four people, or five, or seven, and suddenly you’ve got a lot of plates to spin, and all of them think they’re the protagonist. But sometimes you’re going to have to write it.

As with all dialogue writing, the best way to learn the skill is to spy on your friends and enemies. But the big dramatic ensemble conversations that you need in a piece of fiction aren’t something you tend to come by a lot if life is going even remotely well.

Work meetings? Maybe your boss and that one guy everyone can’t stand will converse a lot while everyone else is thinking about what they’ll have for dinner. Going to the pub with your friends? Conversation quickly breaks down into lots of two-person conversations anyway, and again, unless things are going badly, there’s probably not the kind of high dramatic stakes that will inspire you.

But if you ever sit back at your bi-weekly/monthly tabletop session right before a big fight (or opening any door) you will find an excellent opportunity to observe human interactions.

Decision-making in a high-pressure environment, tactical discussion, and the ways that interpersonal dynamics can interfere with strategic thinking. It is all on the table (literally).

I lied when I told my regular Pathfinder party that D & Deception was a carefully crafted character assassination of each of them, because I wanted to trick them into buying the book. But throughout writing Fermi’s Progress and Fermi’s Wake, my memories of playing with that group have informed how I write big group decisions where everyone’s preferred MO clashes with each others, which is what the Fermi is all about.

If you want to see my devastating character assassination of my RPG group, and hang out with the crew of the deadly starship Fermi, Fermi’s Wake: D & Deception is out now. You can buy it individually or as part of the Fermi’s Wake season pass at Scarlet Ferret, which means I get more royalties and you get a bonus short story, or you can buy it from Amazon here.

Fermi’s Progress is also available as a season pass from Scarlet Ferret (which includes all four Fermi’s Progress novellas in one volume), and can be bought as a paperback from Amazon.