Mickey 17 and the Campaign Against Horizontal Spaceships

- Uncategorized

- March 11, 2025

On Friday I went to see Mickey 17, Bong Joon-ho’s adaptation of Edward Ashton’s novel Mickey 7. It’s a great movie that justified the hype it’s received. It made quite a few changes to Ashton’s novel, Bong clearly had his own story he wanted to tell, but faithfulness to the source material isn’t actually a virtue in itself (even if, personally, I preferred the book version of the story in a few elements).

But there was one change that irritated me, and has continued to irritate me no matter how much I have tried to move on and live the rich, fulfilling life I deserve.

It’s the windows on the spaceship.

We don’t get to see much of it – most of the action in Mickey 17 is confined to cramped, windowless corridors or freezing expanses of alien planet, but during the EV sequences early in the film you glimpse them, and your suspicions are confirmed when the ship lands on the planet.

The windows, and by extension, the internal decks of the spaceship, are orientated horizontally along the ship, with the floors going from back to front.

The Gravity of the Situation

The implications of that deck arrangement are straightforward – the crew of Mickey’s colony ship, as well as all their favourite objects and belongings, are held down by some sort of artificial gravity.

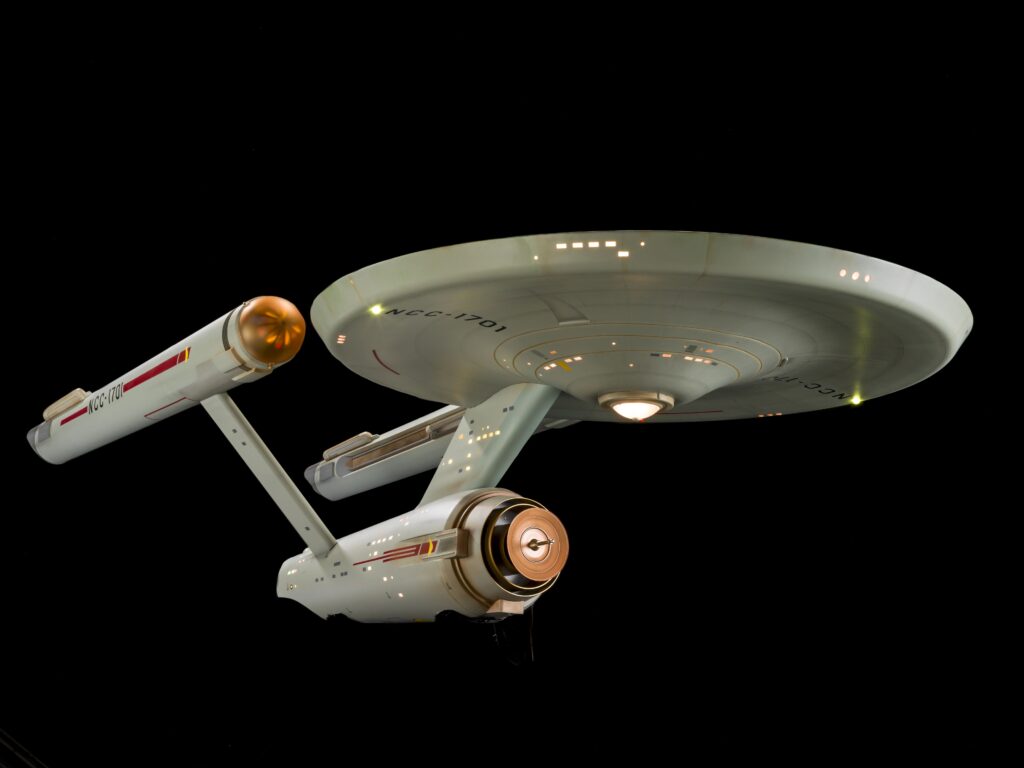

This is hardly a break from the norm. If it’s good enough for the crews of the Enterprise, Battlestar Galactica and Imperial Star Destroyers it’s good enough for Mickey. Except these are all spaceships with FTL drives and usually forcefields and a host of other science fiction doo hickeys to make “gravity plating”, or however you want to justify it, seem a bit more plausible.

Still, it makes sense. Filming in zero-G is expensive and awkward. We also have plenty of evidence that long-term zero or microgravity exposure will lead to all sorts of healthy complications, quickly rendering the regularly reprinted Mickey the healthiest member of the colony. But you don’t need “gravity plating”.

In Mickey 7, gravity on the long journey to Niflheim is provided by the ship’s constant acceleration, and then, once the ship reaches its halfway point and endures a brief period of zero-G as it flips over, constant deceleration. You know how you feel you’re press back into your seat when a car accelerates? Same thing.

It’s a solution we see used heavily in The Expanse, particularly aboard the show’s hero ship the Rocinante. It is laid out like a tower, with the “bridge” at the top and the engine as the bottom. On larger habitats the series also uses rotation to generate gravity (like how water will stay in a bucket if you swing it round on a string).

That is a solution we have seen plenty of times in cinema, from 2001: A Space Odyssey, to The Martian, The Europa Report, Mission to Mars, and creepy “Chris Pratt liked your social media profile so he’s going to kill you” movie, Passengers. It is also how the characters in my Fermi’s Progress stories keep their feet on the ground.

Acceleration and centrifugal gravity are not just scientifically more plausible – they make for better cinema. By making up, down and forward arbitrary designations, you’re giving your characters a more visually interesting world, and one that reflects that the certainties and assumptions they might have are not to be trusted. Frankly, one of the best pieces of science fiction cinema made is the scene of Frank Poole jogging around the rotating habitat of 2001’s spaceship Discovery.

With such easy and more interesting solutions available for space gravity, one wonders why Bong didn’t adopt it for the movie. But he’s hardly the first.

A Sea of Stars

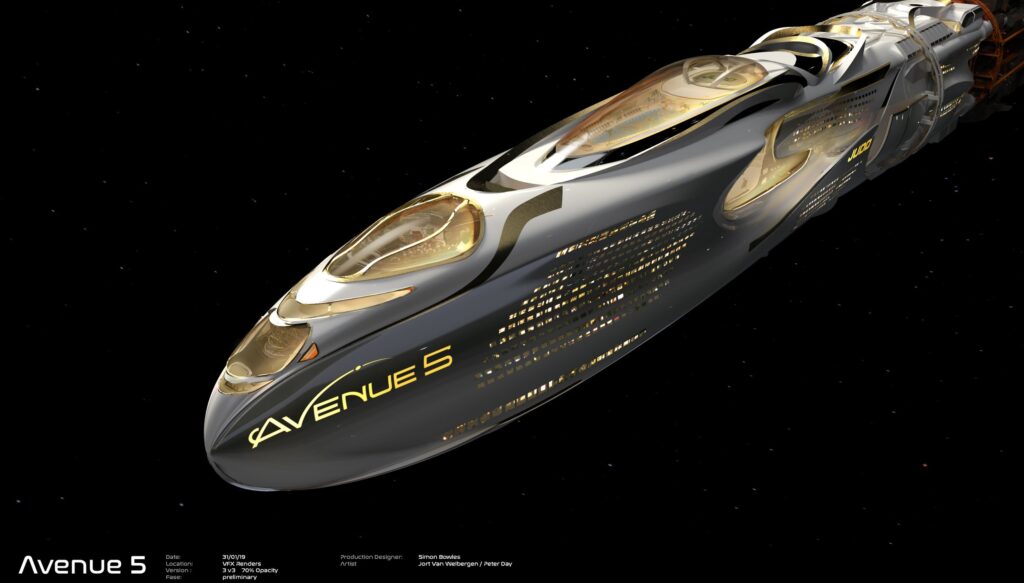

The comedy series Avenue 5 is set in a world if anything even less high tech than Mickey’s.

Taking the premise, “What if Apollo 13 but it’s a cruise ship?” it has no interstellar travel, just a round-the-solar-system cruise, and they can’t even get that right. As TV sci-fi goes, it gets a lot of details right that others don’t even both with – time delays on communications once you reach distances of light minutes away, the way that bodies and sewage ejected into space find themselves orbiting the ship for all eternity.

But the ship shares a deck plan with the U.S.S. Enterprise and the H.M.S. Titanic. And that’s the clue. A lot of science fiction, a lot of science fiction, treats space as an ocean, extremely literally. There’s a reason why, in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, it is considered an ingenious strategic gambit when Spock suggests attacking from above or below rather than the front or side. It is the same reason why, when a big spaceship gets hit in Star Wars, it begins to tilt as if the hull damage is below the space waterline. In extreme circumstances, we might treat a spaceship as an aeroplane, but even then we often simply can not be bothered to think about how ships work in a world without an up or a down.

The most egregious example is in the Jordan Peele Twilight Zone reboot episode “Six Degrees of Freedom”. It is about a Mars mission, about the most basic, mundane sci-fi space mission as you can get.

The episode opens on a launchpad, the crew lying back in their seats, pointing to the sky like every Apollo and space shuttle astronaut ever.

Then the camera passes through the cockpit, into the kitchen and living area behind it (and regular readers will know how much I love a spaceship kitchen), and the camera reorientates because, naturally, the room goes from the front of the spaceship to the back. They have a hand-waving line about establishing artificial gravity in a bit, but we’re not there yet.

And standing in the kitchen is Jordan Peele, doing his Rod Serling narration to camera.

Which is fair enough. We all know the Rod Serling is not confined to our laws of physics. The show is not called The Regular Zone.

But before the camera reaches him, it pans past some kitchen implements, in a cup, on a shelf.

How Hard Do You Want It?

Now it probably sounds like my complaint here is “realism”. It’s not. I love spaceships that whoosh when they fly past and go bang when they explode. I think Moonfall is a great time and does exactly what it sets out to do.

Like most binaries, the difference between “hard” and “soft” science fiction is entirely artificial. We are all just out here trying to blag our audiences into thinking that a thing that is not real could actually be real. We do the research and find plausible scientific explanations and potentially possible technologies to show how everything could work, but this is all marketplace patter used to disguise the person hiding inside the Mechanical Turk (in sci-fi, that person is a wizard).

We are still essentially running the same con Mary Shelley did when she used recent experiments in galvanism to add a veneer of frightening plausibility to her story about a vengeful golem.

But the patter is not unimportant. The patter is how we negotiate with the audience, and set their expectations of the possible.

Complaining about space fighters moving like World War One bi-planes in Star Wars is like complaining that the Sheriff of Nottingham’s troops look like riot police in Otto Bathurst’s underrated Robin Hood movie. The opening scenes of that movie don’t make the Crusades look like Bravo Two Zero because Bathurst has a poor grasp of history. These things are filmed this way to signal to the audience “You don’t think this film is about Prince John’s taxation regime do you?”

But that cuts both ways. As we’ve already said, “hard” sci-fi is just one of many costumes science fiction puts on to sneak past the bullshit sensors. Not just giving us rotational and acceleration-based gravity, but giving us a depiction of space travel that hinges on the Newtonian maths of fuel burns and momentum.

It creates a world where problems can’t be solved by someone reciting technobabble over a touch screen. Where the distance from Earth to Mars is traversable, but also an impossibly vast and hostile distance. Characters here know that if something goes wrong, nobody can help them, and that any solution they come up with has to line up with physics as we understand it.

In Mickey 7, we are shown a distant future where humanity has spread itself far among the stars. In the novel, Mickey’s colony is not from Earth, but Earth’s great-great-great-grand-colony. The Expendables are not a new and exciting tool spearheaded by the head of the colony, but a galaxy spanning system Mickey can never hope to overthrow. This all frames the story differently to Mickey 17, and that it takes place in a world as subject to Newton’s laws as ours helps drive it home.

The Expanse’s use of “hard” sci-fi trappings is to similar ends.

But when the space travellers in that story encounter an artificial wormhole built by ancient aliens, it changes the way the universe works, just as Mickey’s universe changes when he encounters sentient, centipedes.

You know what you call it when someone encounters something that changes the way the universe works?

Science fiction.

Neither Fermi’s Progress, or its sequel series, Fermi’s Wake, feature artificial gravity plates. Instead they feature of prototype Faster-Than-Light spaceship that inadvertently vaporises every planet it encounters. If you’ve enjoyed this blog, you’ll enjoy those stories.

To read Fermi’s Progress, buy the season pass from Scarlet Ferret (which includes all four Fermi’s Progress novellas in one volume), or the paperback from Amazon.

To read Fermi’s Wake, buy the Fermi’s Wake season pass at Scarlet Ferret, or get all the individual novellas in the series from Amazon here.