“Intelligences Greater Than Man’s and Yet as Mortal as His Own”

Part 4: Beyond Imagination

- Uncategorized

- February 11, 2021

We’re coming towards the end of this little series now. We’ve looked at how we might make aliens that look actually alien, rather than like actors with forehead make-up. We’ve looked at how to construct an alien culture (and what not to do), and how we can look at out own unexamined assumptions to see what rules we can break.

Today we’re going to push that even further, looking at aliens that are so alien we might not immediately recognise them as lifeforms at all.

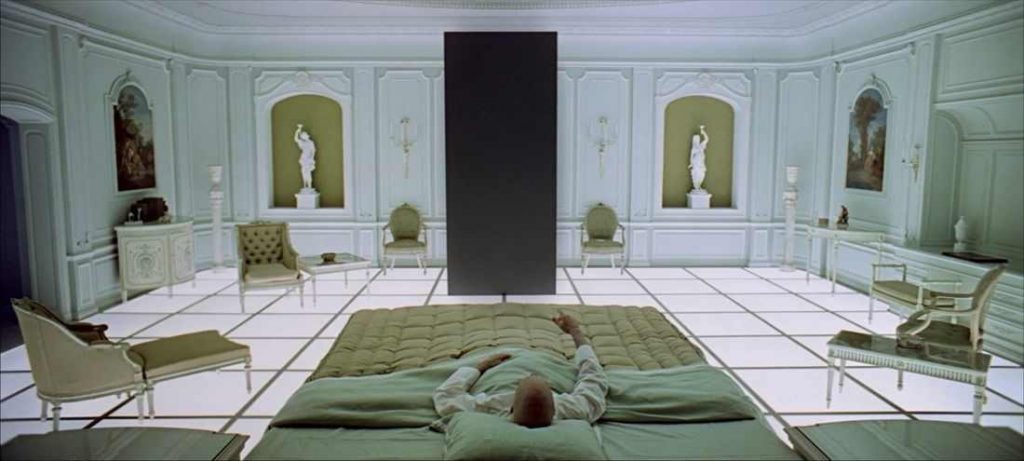

An easy way to create “alien” aliens is to put them so far outside of human perspectives that we can’t even guess at their motives. The Monoliths in the historical drama, 2001: A Space Odyssey, the visitations in Roadside Picnic, or the Spindle Kings in Terry Pratchett’s Strata.

These aliens are so much smarter and stranger than us as to be unknowable. They aren’t glowy Jesuses, their morals and purposes are completely mysterious to us.

But this feels like a bit of a cheat to me. It’s like writing a horror story where something in the house is making a mysterious thumping noise, but you never found out what it is. Yes, it can be powerful letting the reader’s imagination do the work, but you’re a writer, it’s supposed to be your imagination doing the heavy lifting.

The way we do this is by going back to the “breakable rules” we covered last week and seeing how much further we can go. We can go so much wilder than gender, economics and politics, which even on Earth we still, after a little bit of thought, realise are mostly made up. Aliens won’t necessarily even have the same concept of self that we do. While we will use different words depending on which religious or philosophical brand we sign up to, humans largely think of themselves as ghost monkeys piloting a vehicle made out of meat. We see another person, and we think of them as separate to ourselves, because however close their meat is to ours, even if they are our identical twin, we still essentially recognise that they are driven by a different ghost monkey.

But this is far from the only arrangement. There are hive minds when you have one ghost monkey controlling either the whole species, or different ghost monkeys controlling small groups of meat puppets. Ghost monkeys might blend and merge with each other, swapping memories, sensations, skills or personality traits whenever they meet.

Or an individual might be a meat vehicle with a number of different ghost monkey drivers, my own belief in Drunk Chris and Hungover Chris taken to its natural conclusion.

In fiction we tend to see the Hivemind as the ultimate dystopia, because as a culture we can’t seem to imagine anything worse than the possibility we might not be a special and unique snowflake. But at the same time “Hivemind” is already a word you’ll find being used over and over on Twitter, as we become more interconnected all the time. Maybe it’s time to ditch the “but that would be evil” view of the hivemind and ask what that mind might look like? Would you end up with an evil, all-powerful space Hitler, or the ultimate neurotic, containing the self doubts and contradictions of an entire civilisation? Would it still create art, just for the satisfaction of creating, or would creating things within its own imagination for itself be enough? How do you form a culture when you don’t really have anybody to argue with?

Okay, so let’s go a bit further out there and start thinking about aliens that don’t even obey the same physical laws as us. The Flatlanders are a good example of this, so good that I haven’t been able to get my head around them yet, so instead we’re going to talk about linear time.

If you think about it, viewing time as linear is pretty weird. It’s a lifespan that’s a lot like the suddenly materialised whale in Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy: You are born, then you travel in a straight line in one direction until you hit the ground.

Viewing time in a non-linear fashion doesn’t necessarily mean time travel (which is good, because I’ve already given my talk on time travel today) but if you see time as a progression of moments trapped in amber, that changes your perspective on everything from Spoiler Alerts to death.

The best-known example of this right now is the living embodiment of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, the hexapods from Arrival (or The Story of Your Life). But there are also the Prophets in Deep Space Nine, who spend a long time puzzling about the linear nature of the humans and Bajorans, apart from when they don’t for plot.

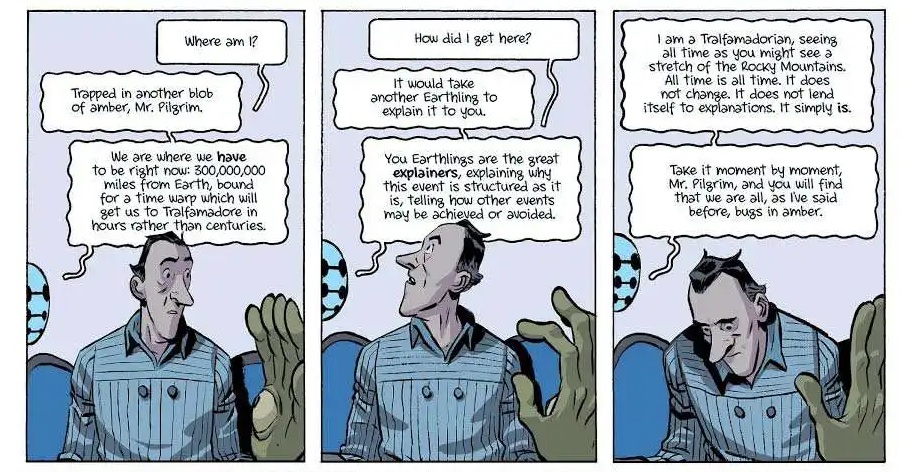

But my favourite example of this is the Tralfamadorians of Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five (there are various other Tralfamadorians in other Vonnegut books, but today we’re going to stick to talking about these ones).

These Tralfamadorians look like sink plungers with rubber gloves on the end of their handles, and have no concept of linear time (the image above is taken from Ryan North and Albert Monteys’s excellent graphic novel adaptation of Slaughterhouse Five). What’s great about the Tralfamadorians though, is that this solves none of their problems. Where Billy Pilgrim expects them to be glowy white space Jesuses who can teach humanity the importance of World Peace, the aliens are quick to disillusion him. Here’s a brief extract:

‘But you do have a peaceful planet here.’

‘Today we do. On other days we have wars as horrible as any you’ve ever seen or read

about. There isn’t anything we can do about them, so we simply don’t look at them. We

ignore them. We spend eternity looking at pleasant moments-like today at the zoo. Isn’t

this a nice moment?’

‘Yes.’

‘That’s one thing Earthlings might learn to do, if they tried hard enough: Ignore the

awful times, and concentrate on the good ones.’

‘Um,’ said Billy Pilgrim.

If you’re currently in the middle of a war, this alien wisdom isn’t all that useful to us linear time creatures.

"Intelligences greater than man's and yet as mortal as his own."

The title of this series invoked the quote “Intelligences Greater Than Man’s and Yet as Mortal as His Own”, a line from War of the Worlds, one of the first and best depictions of intelligent life from a planet other than ours.

That quote tells you everything you need to know about the Martians. They’re smarter than us, but they’re still basically very intelligent animals, with all that this entails. They are a constant balance between being a reflection of the human race, while at the same time showing that things we take as givens within the human race need not necessarily be so.

They look non-humanoid, with gigantic heads, tentacle arms, beak-like faces and reproduction through “budding” rather than any breeding habit we might recognise. They feed by mechanically drawing blood from Martian animals we would recognise as humanoid, but are no more malicious about it than we are when eating rabbits. They have spaceships, heat rays and giant robot walkers, but they have never developed the wheel. And although they are the aggressor the narrator points out time and time again that they are doing nothing the British Empire and the human race in general don’t do as a matter of course. As alien as the Martians are, they are not directly opposed to human nature, they simply do it better than us. Because again, that’s what aliens are great at: Showing us what humans look like from the outside.

Okay, I’m wrapping this up now, and there’s so much I haven’t covered. I haven’t covered the existence of non-carbon based life forms, or even gone into much detail about the creatures we might not recognise as life when we meet them. We haven’t covered the possibility of mechanical life, of von Neuman machines that have long since outgrown their creators, if they had them in the first place. I haven’t covered the Mantis Shrimp, a creature that has sixteen colour receptive cones in its eyes relative to our rather boring looking three. That’s a creature on this planet that can see thirteen colours you literally cannot imagine. There are so many different ideas to explore, and even once you’ve decided what your aliens look and think like, you still have to give them individual personalities (if they have them) and storylines and a purpose as you figure out what their actual story is going to be, because no matter how well executed your aliens are, you’re still going to need one of those.

But before I finish I just want to give you a few things to remember, a few golden rules to avoid breaking.

An entire planet doesn’t have just one culture.

An entire planet doesn’t even have just one type of weather

An entire species is going to have more than one type of emotion or personality type.

And their planet is not Earth, the gravity, the seasons, the day lengths and even the spectrum of colours may be totally different to what you’ll find here.

But finally, robots and wooden boys made by humans might wonder what it means to be human. We’re the sort of bastards that would probably make a new life form to wonder things like that. But no other creature in the universe cares.