Welcome to the Treehouse – Introducing Fermi’s Wake: Graveyard Orbit

- Uncategorized

- February 12, 2025

When I first told a writer friend that I was going to do a “Simpson’s Treehouse of Horror” for the next round Fermi’s Progress stories, he laughed.

“I love that. You’ve got characters telling each other stories that reveal their character on a long journey and your go-to isn’t ‘Canterbury Tales’, it’s ‘Simpson’s Treehouse of Horror’?” he asked.

This friend is a really nice guy, he was more amused than mean, and he doesn’t deserve to be cast as the rhetorical foil in a self-aggrandising author anecdote, so I will leave out the incredibly witty reply I thought of much later.

But he hit on an important distinction. Fermi’s Wake: Graveyard Orbit (Available to preorder and Scarlet Ferret and Amazon) is a Simpson’s Treehouse of Horror episode, not a Canterbury Tales episode. The Canterbury Tales is the grandaddy of stories where characters tell stories, it codified the way that those stories can switch form and genre, sometimes to tell us something of the storyteller, sometimes to show them needling at another member of the party. But when those stories confine themselves to the spooky, that is a genre all of its own.

The Simpsons is not the only one to do the format, of course. Any TV show looking to do a Halloween special is likely to try the format, from Arthur with “Arthur and the Haunted Treehouse”, to Community (of course Community) with “Horror Fiction in Seven Spooky Steps”. You’ve seen it in movies like 2017’s Ghost Stories, or 2019’s far worse and horribly transphobic Tales from the Lodge, or 1997’s Campfire Tales. It is a format that loosely fits Jonathan Sim’s “Thirteen Floors” anthological novel (which contains some of the most horrifying acts you will ever find yourself cheering on in a book).

And there’s a reason why we have seen this format used with horror stories far more than there are, for instance, stories where a bunch of couples gather to share the rom-com story of how they met (although now I kind of want to see that movie).

Part of the reason goes back to Canterbury. This storytelling is adversarial (which again, would totally work for that rom-com by the way). Our storytellers are not trying to make people laugh, or make them happy. You’re trying to scare the shit out of them. Every story in these exchanges is a move of a game piece, a blow in a fight.

Also, it is a weird quirk of horror stories that they always feel more true if someone is telling them to you. That is why The Rime of Ancient Mariner must be told by a dishevelled stranger to one in three people at the door of a wedding. It’s why Stephen King has “The Breathing Method” and “The Stranger Who Would Not Shake Hands” told as tales in that mysterious gentleman’s club that might not quite exist in our reality.

Even one of the all-time great horror stories (and not coincidentally the ancestor of all science fiction), gains just that little bit of extra menace because we know that it was conceived in a dream at a rainy villa after Lord Byron proposed a ghost story competition.

But the third reason, which by the way, completely contradicts the first, is that these stories of horror have a different flavour when told by the person who witnessed them. These are not uncouth “needless to say, I had the last laugh” anecdotes about something a writer friend said when you told them your idea. They are not jokes (although perhaps another time we might talk about why horror stories and jokes feel so structurally similar).

For all that that each story at the campfire is an attack on the audience, it cuts both ways. More often than not, these stories are confessions. You cannot scare people with a tale heroism. These are stories a failure, of cowardice, hubris, of ignorance of the terrors creeping in all around you until it was too late. By definition, unless you want to pull an extremely cheesy twist, the narrator of your story has survived the ordeal they describe, so the question is “At what cost?”. What did they have to do? What did they leave behind?

These are the questions asked in the stories the Fermi crew will tell while sat around the spaceship’s sofa, ignoring the Tom Cruise “Dark Universe” version of The Mummy. The monsters in these stories might seem familiar – there are vampires, Frankensteins, clandestine alien invasions and Lovecraftian monsters. Except maybe not, maybe these are just labels and tropes the storyteller puts on much stranger horrors, in an attempt to make them small enough for the human mind to cope with.

After all, what else are monsters for?

You can buy it individually or as part of the Fermi’s Wake season pass at Scarlet Ferret, which means I get more royalties and you get a bonus short story, or you can buy it from Amazon here.

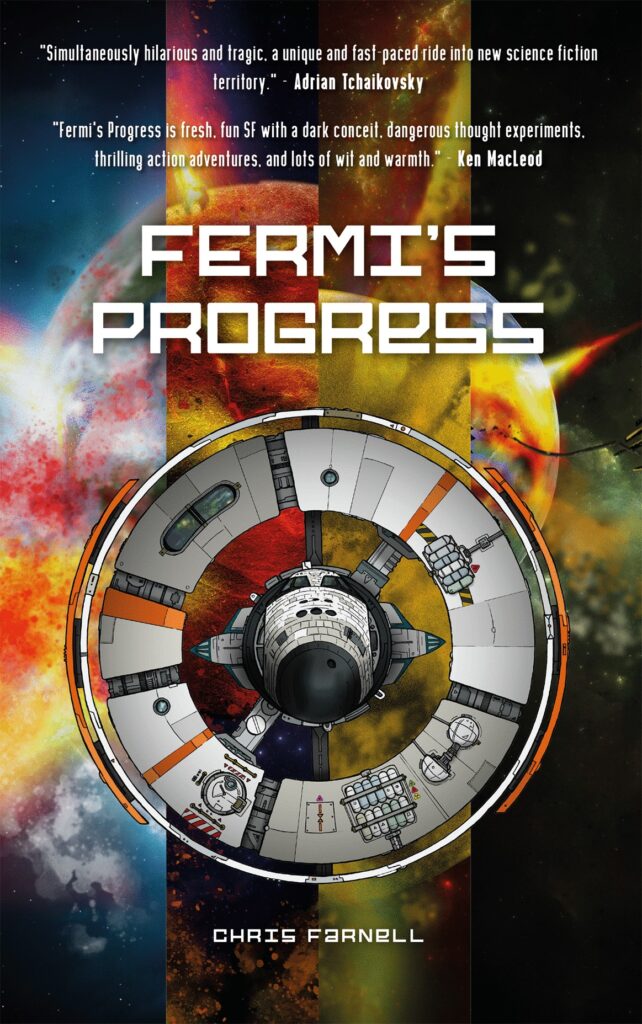

Fermi’s Progress is also available as a season pass from Scarlet Ferret (which includes all four Fermi’s Progress novellas in one volume), and can be bought as a paperback from Amazon.